Outcomes-Based Assessment (OBA) has been on our educator radar for years. I have the pleasure of working with groups of teachers throughout Saskatchewan to dig into what we know, what we wonder about and examine logistical barriers or problems to solve in order to move forward.

What do teachers know? What do teachers wonder about?

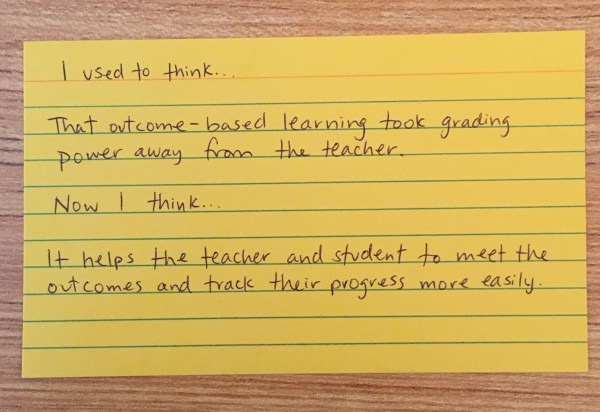

Professional development needs to surface teacher knowledge, including any misconceptions that might exist. Too often, professional learning facilitators assume that educators do not know anything so begin from the beginning… or assume that educators know everything and are choosing to resist change. I would argue teachers know a lot… and they, as a collective, want to do best for students and learning. Just like in a classroom, misconstruction of knowledge can occur. It is our job as learning facilitators to use our formative assessment skills to expose understanding and misunderstanding so that we know what to do next.

Professional development needs to surface teacher knowledge, including any misconceptions that might exist. Too often, professional learning facilitators assume that educators do not know anything so begin from the beginning… or assume that educators know everything and are choosing to resist change. I would argue teachers know a lot… and they, as a collective, want to do best for students and learning. Just like in a classroom, misconstruction of knowledge can occur. It is our job as learning facilitators to use our formative assessment skills to expose understanding and misunderstanding so that we know what to do next.

When teachers are asked, What do you know about Outcomes-Based Assessment? Their answers might be similar to those generated in NLSD:

It is important when broad statements are made that they are clarified by the group.

- Clarification may be needed on the term ‘learning behaviours’. These include things like attendance, behaviour, neatness, compliance with assignment expectations. Schools or systems may have other ways to communicate these ‘Hidden Curriculum’ expectations to students and parents outside of their academic achievement scores.

- Clarification may be needed around the idea that assessment is based on “where they are at right now… can change over time”. An example where a student shows competency later in the year after that unit of study has been completed. This may raise some logistical questions around how this would work within a student information system or what impact this idea has on reporting. Once specific questions or logistical barriers surface, it is possible for a school or system to determine procedures so that they can have consistency.

As Tomas Guskey states, there is NO best practice in grading. There are ‘better’ practices that we want to embrace, but there is no universal, standardized and mechanical way to generate a grade for our students. This was an empowering point with teachers to know that their professional judgment, based on an understanding of curricular outcomes and observable student behaviours, is the most important assessment practice.

Along with what educators know, it is vital that we surface what they wonder about. Questions can frame teachers’ professional inquiry for a day of learning, as well as indicate what they need to be emphasized within the agenda. Typical questions around this topic may be:

- How do I translate an outcomes-based assessment rubric into a %?

- How do we gather, translate and score observations and conversations so that they ‘count’ like products?

- What might a teacher daybook/unit plan look like using outcomes-based assessment?

- Is all assessment outcome-based assessment?

- What do we do if an assignment is late or not handed in?

- What is the minimum/maximum number of indicators that we need to assess in order to maintain the integrity of the outcome?

- How do we use outcome-based assessment in cross-curricular teaching?

It is important that participants choose which question(s) they are most invested in to solve, and provided time within a professional learning experience to discuss possible solutions with colleagues.

Assessment practices are founded on both beliefs and knowledge. A Talking Points Strategy can help to have small groups explore and surface their beliefs about assessment.

Starting with Curriculum

Learning targets are based on curricular outcomes. There are a number of different unit and lesson planning templates used in education. One useful process is to use a thinking map. This graphic organizer allows us to see the connections amongst curricular outcomes, instructional activities and assessment criteria.

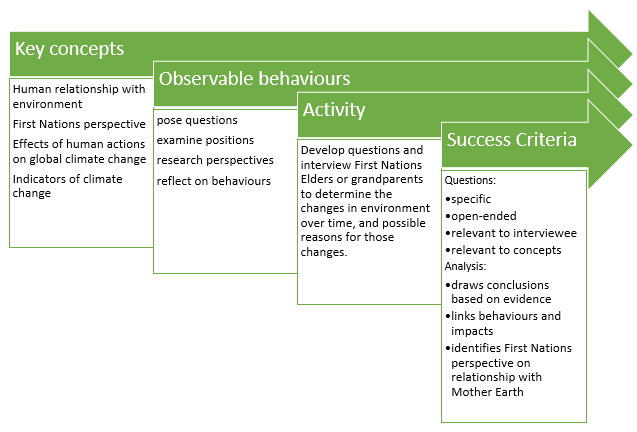

Starting in the centre, teachers can identify the connections between the nouns (concepts) and verbs (observable behaviours) of the curriculum with the activities that allow students to show those behaviours. The assessment criteria should be related to the curriculum rather than the activity.

For example, in Saskatchewan Science 10, one part of the SCI10-CD1 Outcome: Assess the implications of human actions on the local and global climate and the sustainability of ecosystems. Some of the indicators related to this outcome might be addressed in the following progression:

By unpacking into a circular thinking map, it is possible to see how the concepts and observable behaviours work together. This will lead to a holistic view of curriculum that eradicates the question of how many indicators are important to address.

Principles of Assessment

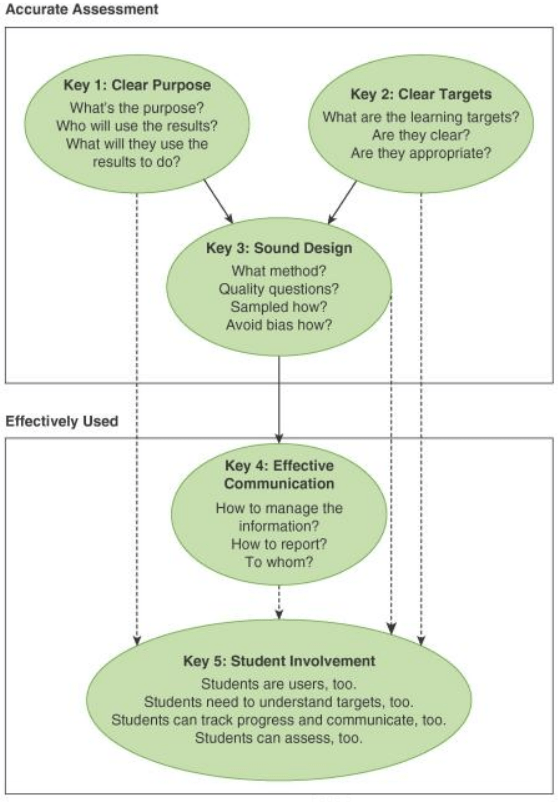

Rick Stiggins has developed a set of key ideas related to classroom assessment:

(Chapuis, Commodore, Stiggins, 2016)

From Criteria to Rubrics

There are a variety of assessment tools, including checklists, portfolios, and rubrics. They all rely on clear learning targets or criteria for student success. What does success look like? What are we looking for?

Expanding on clear learning targets, Sue Brookhart shares some of her ideas on building high-quality rubrics.

Sue Brookhart’s ideas have been incorporated into this simple editable Rubric Worksheet.

Formative and Summative Assessment

Too often, formative assessment is defined as ‘things that are not marked’, while summative assessment is defined as “things that are graded at the end of a unit”. This implies that learners can only show understanding that ‘counts’ at the end of a unit of study. So what happens to all of their thinking, work and brilliance along the way? Is it possible that a learning and assessment experience might be both or either for different students? Is it possible that formative and summative assessment are interconnected?

Definitions

One definition for assessment is the ways in which instructors gather data about their teaching and students’ learning (Northern Illinois University, Faculty Development and Instructional Design Center). This definition implies that assessment’s purpose is multi-faceted – to inform students and teachers regarding student understanding as well as to inform teachers about their practice in teaching. Assessment, whether it is formative or summative, is a snap-shot in time that changes with instruction and understanding.

Formative Assessment

In his book, Embedding Formative Assessment, Dylan Wiliam defines Formative Assessment as:

“An assessment functions formatively to the extent that evidence about student achievement is elicited, interpreted, and used by teachers, learners, or their peers to make decisions about the next steps in instruction that are likely to be better, or better founded, than the decisions they would have made in the absence of that evidence” (Wiliam, 2011).

This definition implies:

- Formative describes the function of the assessment rather than the form.

- Teachers, students and peers might be involved in deciding how to respond to assessment information.

- There must be a responsive action based on the data in order for the assessment to be formative. Responsive actions are instructional in nature.

If formative assessments are designed with no clear decision/action implied, then the assessment is not useful. The five key strategies for improving student achievement through formative assessment are:

| Who | Where the learner is going | Where the learner is now | How to get there |

| Teacher | 1. Clarifying, sharing and understanding learning intentions and criteria for success. | 2. Engineering effective classroom discussions, activities, and tasks that elicit evidence of learning. | 3. Providing feedback that moves learning forward. |

| Peer | 4. Activating learners as instructional resources for each other. | ||

| Learner | 5. Activating learners as owners of their own learning. | ||

(Wiliam, 2011, p. 46)

Summative Assessment

Summative assessment is often described as providing information about or evaluating the attainment of understanding or achievement compared to a standard. Katie White (Softening the Edges, 2017) has created a holistic view of summative assessment as part of a larger assessment cycle.

“We engage in formative assessment, feedback and self-assessment regularly. Only after all this do we verify proficiency with summative assessment. It is at this point that we make professional judgments about whether to re-enter the learning cycle because proficiency has not yet been reached or to transition into enrichment or the next learning goal… Viewing summative assessment as part of a larger continuous cycle frees us to make decisions that are right for our learners and right for ourselves” (White, 2017, p. 139).

(The Learning and Assessment Experience at UNSW)

The goal of summative assessment is to evaluate student learning. When viewed as part of a cycle, we can see that an assessment intended to be summative may, in fact, become formative. Similarly, there may be times that an assessment intended to be formative might become summative if a learner is able to show proficiency during that experience.

If we view the terms formative and summative as how the assessment is used rather than the tool or the intent for use, it can help us to see all experiences as part of a larger assessment plan.

Brookhart, S. (2013). How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading. Alexandria: ASCD.

Chappuis, S. J., Commodore, D. C., & Stiggins, R. J. (2016). Balanced Assessment Systems: Leadership, Quality and the Role of Classroom Assessment. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Guskey, T. R. (2019, February 28). Let’s Give Up The Search for ‘Best Practices’ in Grading. Retrieved from Thomas R. Guskey & Associates: http://tguskey.com/lets-give-up-the-search-for-best-practices-in-grading/

UNSW Sydney. (n.d.). Guide to Assessment. Retrieved March 12, 2019, from UNSW Student Home: https://student.unsw.edu.au/assessments

White, K. (2017). Softening the Edges. Bloomington: Solution Tree.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America: Solution Tree Press.

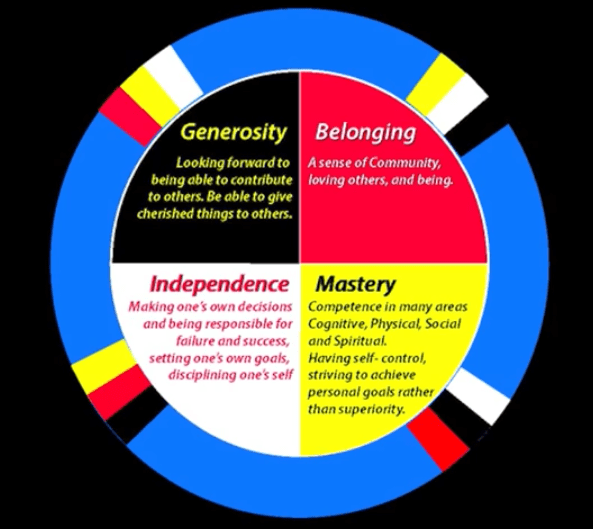

To feel that we belong, we must build relationships with others. Complex kinship systems have existed within First Nations communities for thousands of years (Learn Alberta, 2019). By building a sense of kinship within your classroom, you can ensure that students feel a sense of belonging, culturally socially and physically.

To feel that we belong, we must build relationships with others. Complex kinship systems have existed within First Nations communities for thousands of years (Learn Alberta, 2019). By building a sense of kinship within your classroom, you can ensure that students feel a sense of belonging, culturally socially and physically.

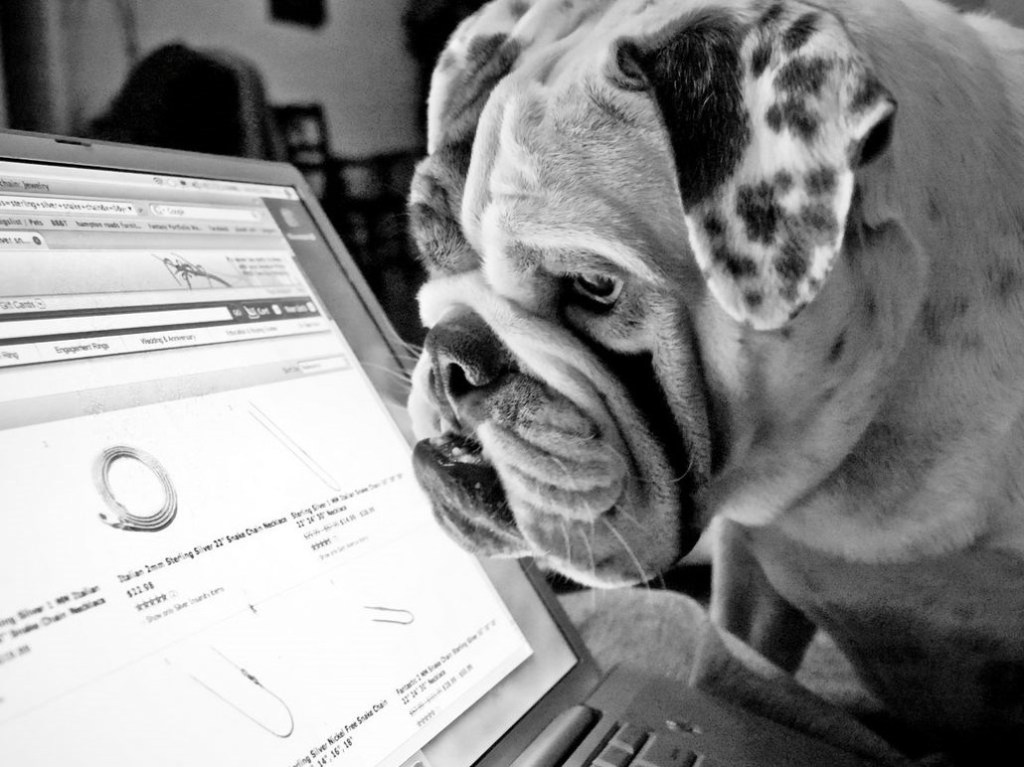

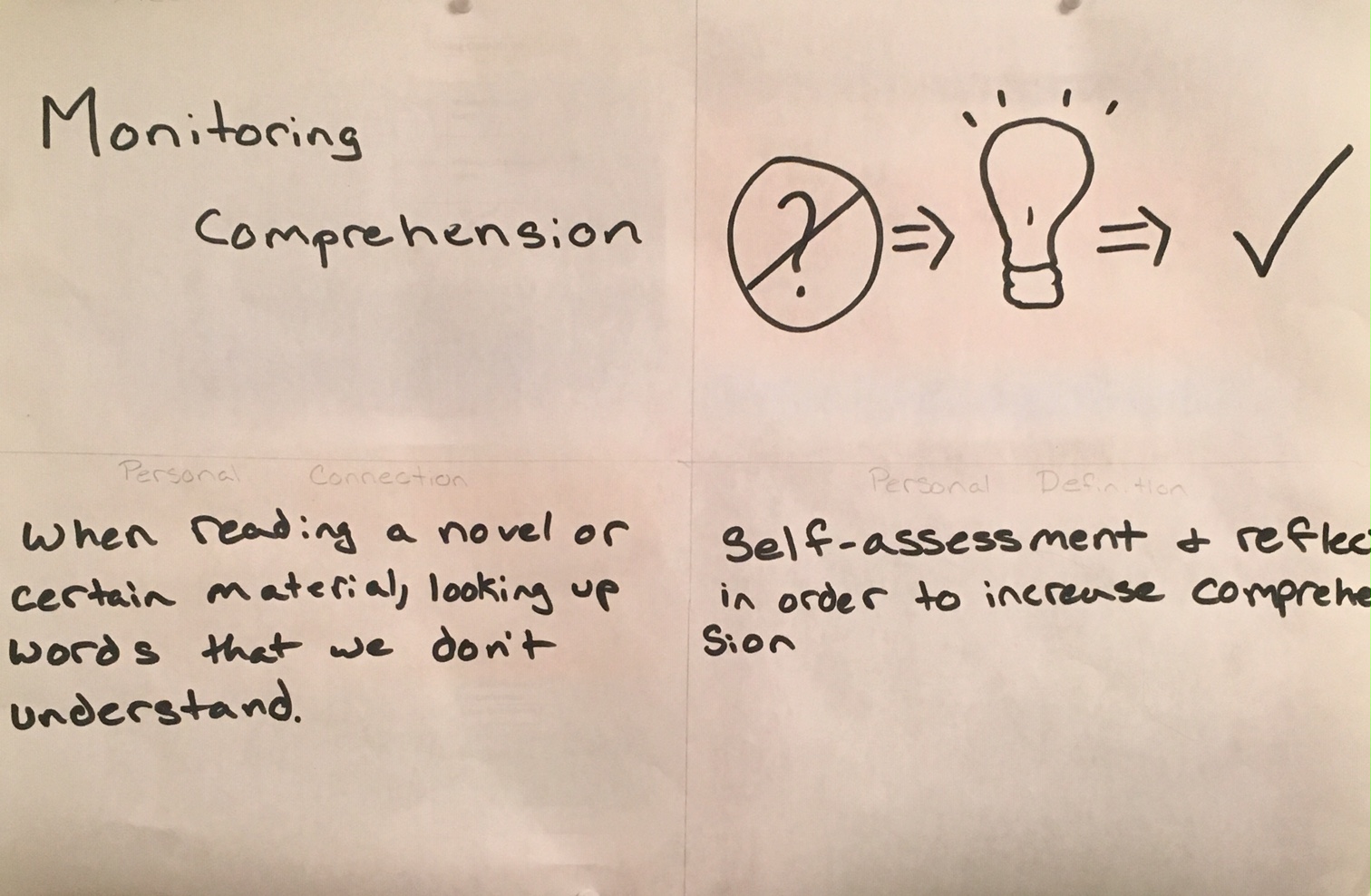

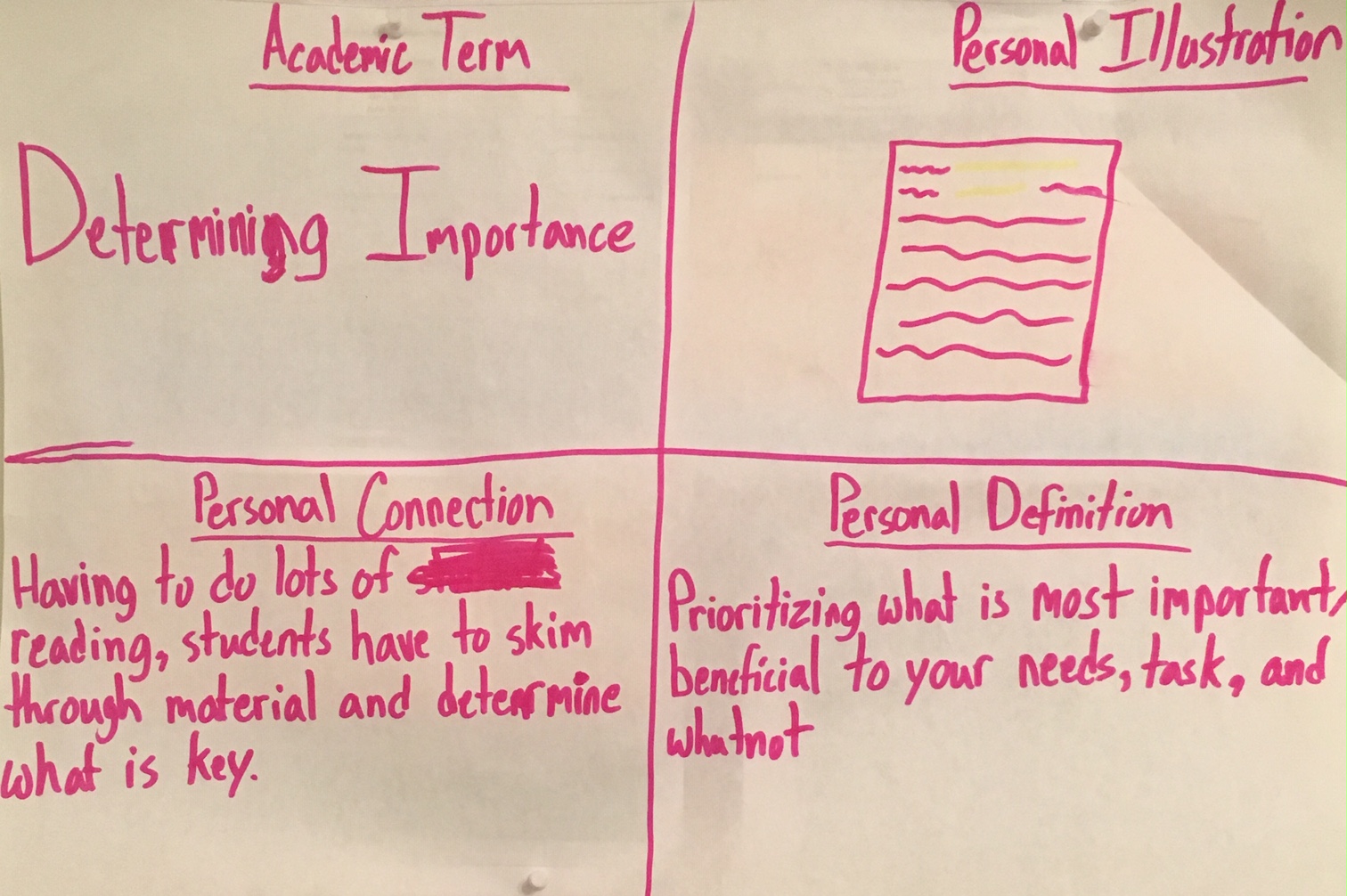

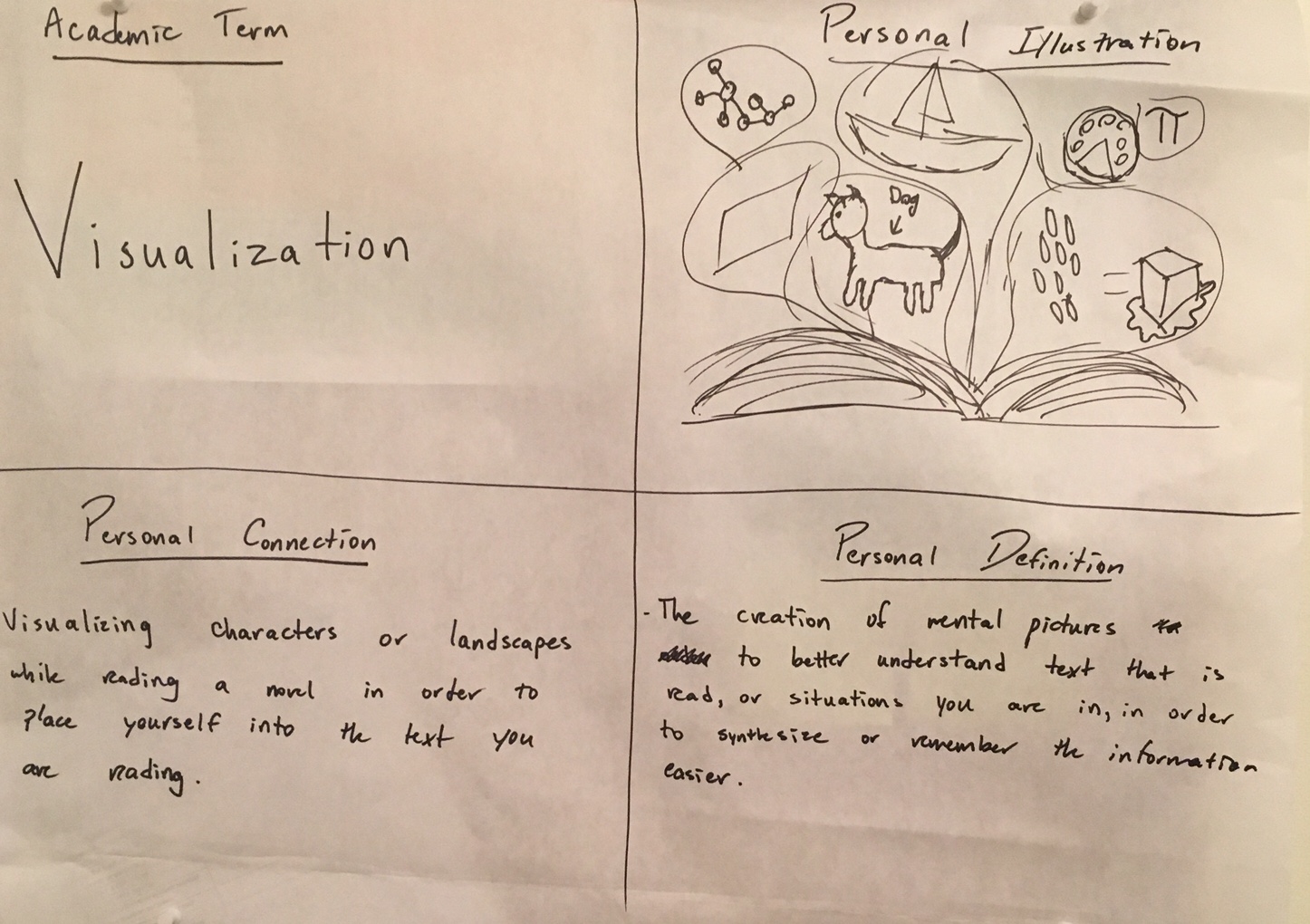

When students are using this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students are using this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students are using this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students are using this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say… When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…

When students use this comprehension strategy, you may hear them say…