The Intent of Strategic Planning

Why create a strategic plan for your organization? Whether you are a small business, school, or international company, a strategic plan helps you to

- Create a shared vision for where you are heading.

- Align actions and impacts from different levels of your organization.

- Simplify decision-making.

- Develop strategies and actions to create a positive future state.

- Outline data and evidence needed to monitor progress.

- Allocate resources to initiatives that will create desired changes.

The Unhelpful Side of Strategic Planning

There is a difference between having an ineffective strategic plan and having an ineffective action within a strategic plan. A working strategic plan will have you gather evidence so that you shift your action plans if a strategy is not having the impact you are hoping for. An ineffective strategic plan results in you having no idea if an action is having an impact, causing us to continue doing and dedicating finite resources to ineffective actions. It is possible to have useful strategies within an ineffective plan, making it hard to create systemic and sustainable change.

An ineffective strategic plan might have the following features:

- It does not reflect current state.

- A working strategic plan reflects current trends, research, and actions being taken within our organizations. It is a living document that shifts over time.

- It does not have buy in.

- A working strategic plan is co-constructed by key stakeholders and is known to all employees and managers.

- It is not used.

- A working strategic plan is used to determine resource allocation, professional development plans, actions of staff, and evidence gathering.

- It is too broad.

- A working strategic plan is simple and focuses on what is most important within your organization. Too many actions and outcomes can spread time and resources out too much and reduce impact of what is most needed.

- It is too vague.

- A working strategic plan has clear actions, impacts, timelines, and responsibilities. Using specific terms can help everyone in an organization know expectations and roles.

- It includes ineffective strategies.

- A working strategic plan is a form of action research. There is no guarantee that an action is going to produce a desired outcome. What is important is that data collection is timely and specific so that your organization can shift strategies if needed. Be aware, however, that often time is needed for implementation and understanding in order to have a desired impact.

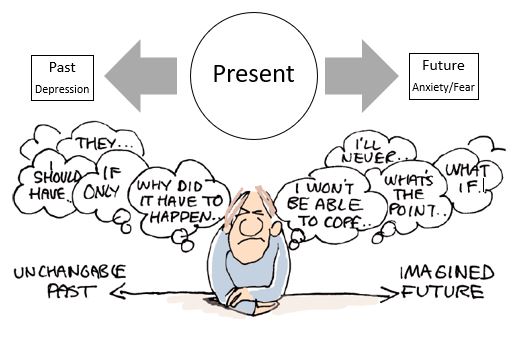

Traditional Strategic Planning: A Deficit View

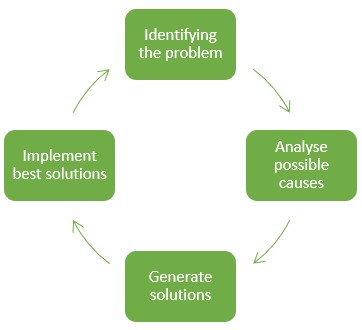

Traditional strategic planning methods go through a cycle of problem identification and solution generation and implementation. Traditional strategic planning methods can lead to a deficit view.

Rather than a deficit view of what your organization is not doing, or not doing well, a strategic planning process should identify where you want to go, what you are already doing that might help, and how you might leverage the strengths of your organization to get there. By empowering your employees with a positively intentional view of your organization’s impact, it is possible to design a future state and the steps to get there. When an organization works with others to achieve its goals, identifying the influence you have on others and the influence they have on you, along with the steps you might take to achieve the influence you are seeking should be a part of your strategic action plan.

Hopeful and Helpful Strategic Planning Processes

There are three key theories of strategic planning that work well when viewed as part of a holistic process:

- Appreciative Inquiry

- Outcome Mapping

- Logic Modelling

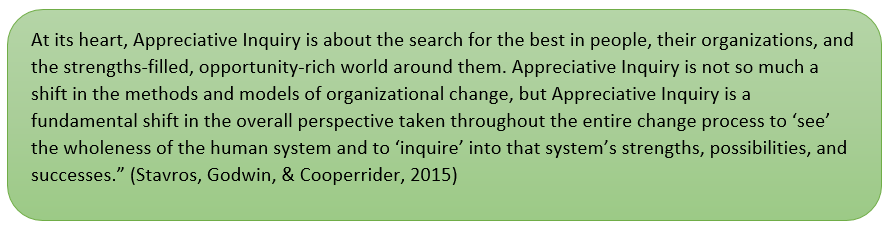

Appreciative Inquiry

There are a series of stages built into the Appreciative Inquiry process:

1. Discovery: What are we currently doing well?

- Ideas are themed and patterns emerge related to organizational strengths. This process allows organizations to focus on positive capacity.

2. Dream: What is the world calling us to become?

- What are the things about our organization that no matter how much we change, we want to continue into our new and different future?

3. Design: What should be our ideal state?

- Co-constructed ideas are grounded in what we are currently doing well, opportunities that are apparent, and organizational capacity.

4. Destiny/Delivery:

- How do we empower, learn and plan for actions to reach our ideal state?

Along with steps in the Appreciative Inquiry cycle, there are a number of foundational principles that guide conversations and planning:

You can learn more about Appreciative Inquiry with the following resources:

- 5 Classic Principles of Appreciative Inquiry

- 5D Cycle of Appreciative Inquiry

- Appreciative Inquiry: Organizational Development and Strengths Revolution

Outcome Mapping

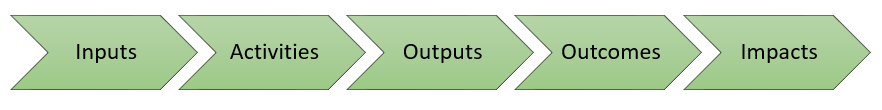

Where does outcome mapping fit into Appreciative Inquiry? Within the Design Phase, those organizations that work collaboratively with other groups in a mutually influential role can utilize facets of outcome mapping to identify actions, outcomes, and desirable observable behaviours. Here is a helpful introduction to Outcome Mapping from Sara Earl.

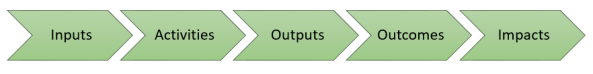

Strategic action planning and program evaluation involve the following steps:

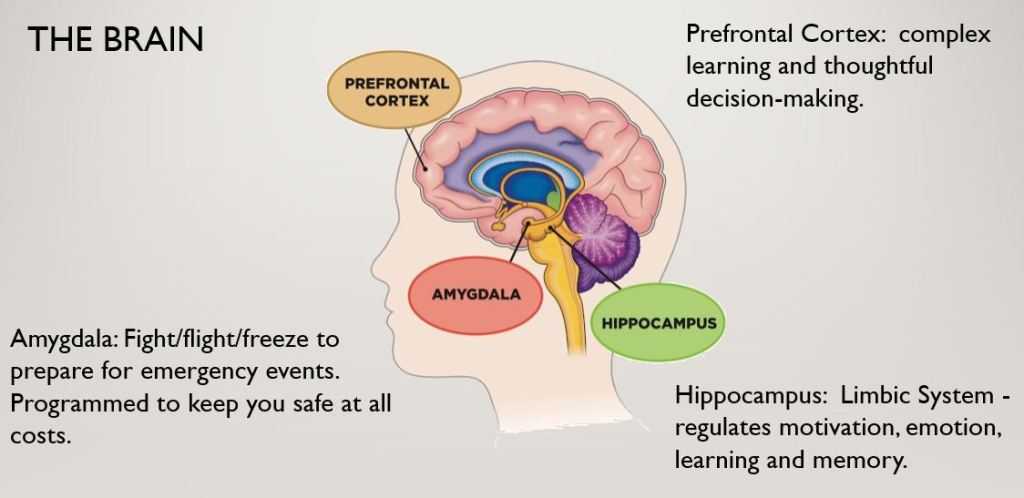

In order to have an impact, people and organizations need to change behaviours. This occurs within the Outcomes stage. When we see ourselves and our organization as a part of a large web of interdependent entities in relationship with one another, we can view change as

- Continuous

- Complex

- Non-linear

- Multidirectional

- Not controllable

People and organizations contribute to the goals of others through influence rather than control.

Program Evaluation as Formative Assessment

Program evaluation is built into strategic planning so that progress can be monitored. When viewed as formative assessment, program evaluation can provide real-time information to inform decisions regarding action plans, inputs, and innovations within your organization. Are the actions you are taking resulting in the outcomes you have identified?

Traditional Evaluations |

Evaluation as Formative Assessment | |

| Purpose | Supports improvement, summative tests, and accountability. Renders definitive judgments of success or failure. | Supports development of innovation and adaptation in dynamic environments. Provides feedback, generate learnings, support direction or affirm changes in direction. |

| Roles & Relationships | Positioned as an outsider to assure independence and objectivity. | Positioned as an internal team function and ongoing interpretive processes. |

| Accountability | Focused on and directed to external authorities and funders. | Centered on the innovators’ deep sense of fundamental values and commitments. |

| Design | Design the evaluation based on linear cause-effect logic models. | Design the evaluation to capture system dynamics, interdependencies, and emergent interconnections. |

| Measurement | Measure performance and success against pre-determined goals and SMART outcomes. | Develops measures and tracking mechanisms quickly as outcomes emerge and evolve. |

| Evaluation results | Aim to produce generalizable findings across time and space.

Evaluation engenders fear of failure. | Aim to produce context-specific understandings that inform ongoing innovation.

Evaluation supports hunger for learning. |

| Complexity and uncertainty | To control and locate blame for failures. | Learning to respond to lack of control and stay in touch with what’s unfolding and thereby respond strategically. |

(Quinn Patton, 2006)

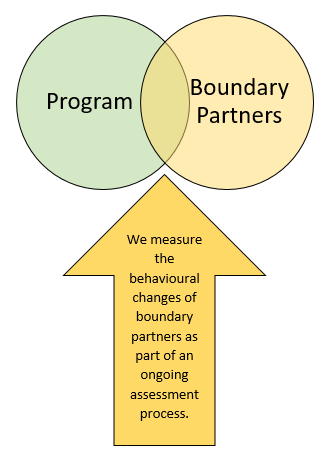

Boundary Partners

Boundary partners are a term used within Outcome Mapping to describe those groups or organizations that you work with directly and anticipate opportunities to be mutually influential. Outcome Mapping identifies behavioural changes in your boundary partners as being a key measurable towards your goals. This is due to the fact that “development is done by and for people. Although a program can influence the achievement of outcomes, it cannot control them. This is because ultimately the responsibility rests with the people affected” (Earl, 2008).

Progress Markers

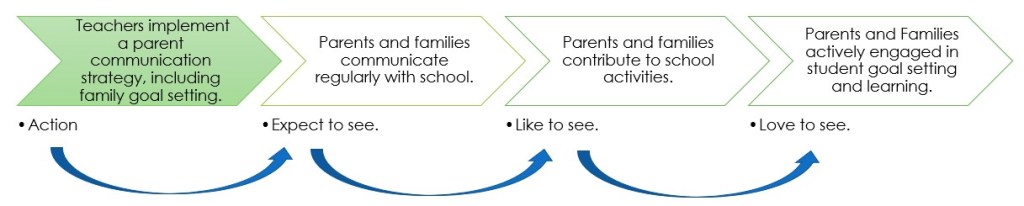

Progress markers (Earl, 2008) are a set of statements describing a progression of changed behaviours in a boundary partner. These describe:

- Actions

- Activities

- Relationships

Leading to the ideal outcome. These markers show the complexity of the change process and have the following characteristics:

- Can be monitored and observed

- Permit on-going assessment of boundary partner progress, including unintended results

The ladder of change can be applied to any progress marker:

- Beginning: Expect to see.

- Mid-Term: Like to see.

- Final: Love to see.

To understand more about Boundary Partners and Progress Markers, watch Sara Earl’s Explanation.

You can learn more about Outcome Mapping through the following resources:

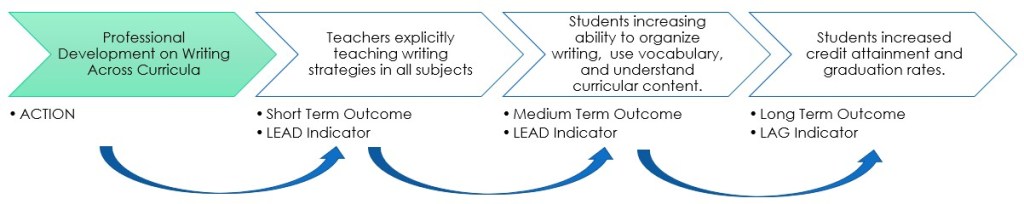

Logic Model

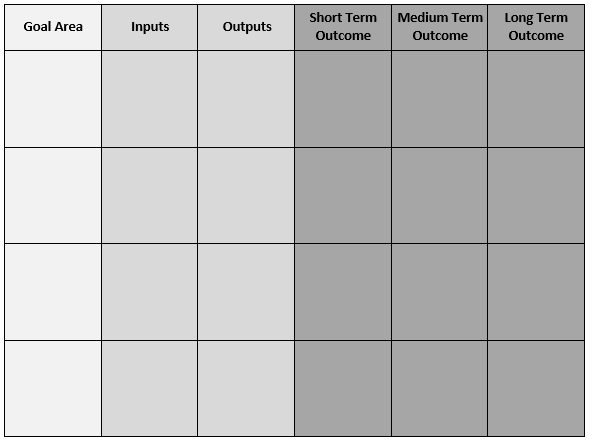

A logic model (Taylor-Powell & Henert, 2008) has many different forms and is a structured way to note specific inputs and activities of an organization and how they lead to outcomes over short, medium and long-term timelines. A logic model can be used in conjunction with other strategic planning processes and is a useful organizer.

You can learn more about creating a logic model through the following resources:

- Compass: What is a Logic Model?

- Creating Program Logic Models: From Theory of Change to Program Models

A Simplified Process

The following Seven Steps for Strategic Planning encompass all three of these foundational processes.

- Area of Focus

- What from your state or provincial priorities resonate with you as an area of need for your students and staff? What are you seeing that indicates this is something your organization should focus on?

- What does your data say? What is your present state?

- What are you currently doing that is particularly effective in this area? How do you know?

- What do your students need you to focus your creativity and energy on?

- What changes would benefit your students and staff?

- Who are you trying to influence?

- For schools, students are the most obvious group you are trying to influence.

- Who else’s behaviour are you hoping to influence through this strategic plan? What individuals, groups, or organizations?

- What might happen if your plan is successful?

- In general terms, what impact are you hoping to have?

- What are the desired behaviours, relationships, beliefs and actions of those you are hoping to influence?

- What would you expect to see? like to see? love to see?

- What might you as an organization DO to contribute to these changes?

- What are you currently doing that works towards these impacts?

- What might you do in the future?

- Who might lead this work? Who might participate in this work?

- What resources might you need?

- What systemic structures might need to be in place?

- What time, money, and other resources are required?

- Where might these resources come from? be reallocated from?

- What are the outcomes you expect to see? There are two ways of viewing outcomes:

- Logic Chain:

- What are the short term, or direct behavior changes that might result from your actions? These are often LEAD indicators (behaviours that might predict a future state or success). These short term outcomes are often teacher behaviours.

- If those happen, then what medium term then long term, or indirect behaviour changes and outcomes might be influenced by your actions? Some of these are LEAD indicators, while others are LAG indicators (behaviours in current state that are based on past actions and performance).

- Behaviour Progression:

- Consider the group whose behaviour you would like to influence. What might you EXPECT to see? LIKE to see? LOVE to see?

- Logic Chain:

- How might you monitor your progress?

- What evidence might tell you about the implementation of your actions?

- What evidence might tell you about the efficacy of shifts in organizational practices and structures?

- What evidence might tell you about your outcomes?

- Changes in behaviours.

- Lead and lag indicators.

- Consider using Wellman and Lipton’s Collaborative Inquiry Method and Collaborative Inquiry Worksheet for investigating your data.

By working through an integrated process for strategic planning, you can empower your organization to look beyond a deficit view of present state and work towards a desired future. By having an action plan for the steps to getting to your future state, it is possible to measure progress as formative assessment, providing a continuous feedback loop for your organization.

References

Earl, S. (2008, June 20). Outcome Mapping Pt 1. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fPL_KEUawnc

MacDonald, N., & Simister, N. (2015). INTRAC: Outcome Mapping. Oxford, United Kingdom. Retrieved from https://www.intrac.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Monitoring-and-Evaluation-Series-Outcome-Mapping-14.pdf

Quinn Patton, M. (2006). Evaluation for the Way We Work. The Non-Profit Quarterly(Spring), 28-33. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from https://www.scribd.com/document/8233067/Michael-Quinn-Patton-Developmental-Evaluation-2006#download

Springboard Social and Behaviour Change (SBC) Community. (2015). How to Develop; a Logic Model. Retrieved from Compass: https://www.thecompassforsbc.org/how-to-guides/how-develop-logic-model-0

Stavros, J., Godwin, L., & Cooperrider, D. (2016). Appreciateive Inquiry: Organization Development and the Strengths Revolution. In W. J. Rothwell, J. Stavros, & R. L. Sullivan, Practicing Organizaiton Development: Leading Transformation and Change (4th Ed) (pp. 96-116). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Inc. doi:https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119176626

Taylor-Powell, E., & Henert, E. (2008, February). Developing a Logic Model: Teaching and Training Guide. Retrieved December 13, 2018, from https://peerta.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/public/uploaded_files/Logic%20Model%20Guide.pdf

Wellman, B., & Lipton, L. (2017). Data-Driven Dialogue. Charlotte: MiraVia.

White, D. (n.d.). Six Reasons Your Strategic Plan Isn’t Working. Retrieved from Allen, Gibbs & Houlik CPA’s & Advisors: https://aghlc.com/resources/articles/2016/6-reasons-your-strategic-plan-isnt-working-160824.aspx

Wilkinson, M. (2011, October 18). Why You Need a Plan: 5 Good Reasons. Retrieved from Free Management Library: https://managementhelp.org/blogs/strategic-planning/2011/10/18/why-you-need-a-plan-5-good-reasons/