As teachers and parents, we have two aspects of trauma to consider and mitigate – the impact of trauma on our own lives and the impact of trauma on our children and students’ lives. As we explore ourselves and the coping strategies that we have developed over time, it is possible for us to reflect on children’s behaviours as ways that they have grown resilience and survival.

This two post series on growing resilience is a collaborative effort with myself, Nancy Barr of NMBarr Consulting, and Kyla Bouvier of Back2Nature Wellness and Events. It is designed to take us on a journey of understanding and empowering ourselves and the children in our care.

Today’s post is the second in this series, and focuses on strategies to mitigate the impact of trauma on our students by creating safe spaces where new neural pathways can be formed.

Trauma, Fear and Learning

Teachers may not deal with trauma directly, bu they are part of the healing process. They give their students order and predictability. After the chaos and confusion of their lives, nothing is more comforting than routines.

Pipher, 2002

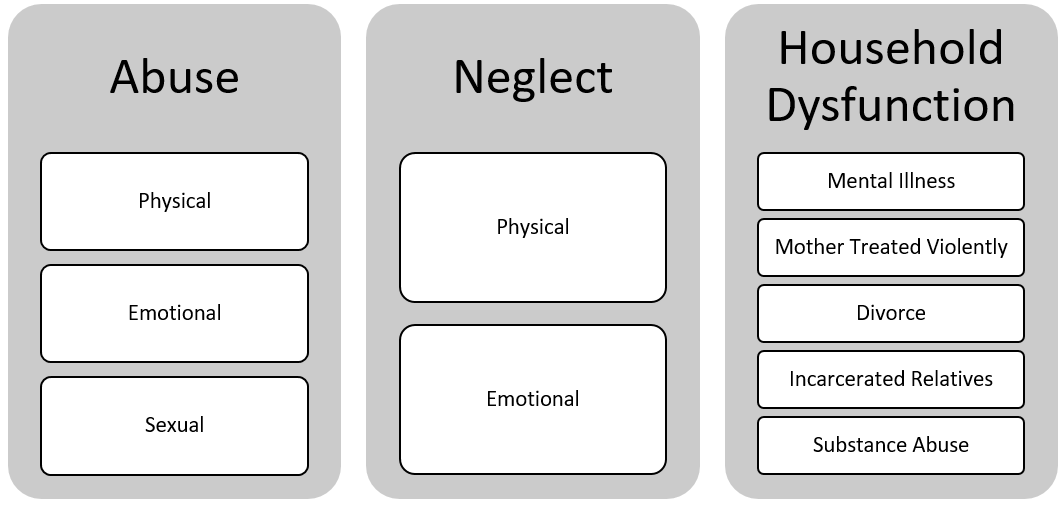

There are many different forms of trauma that our children might experience. These include neglect, abuse, family dysfunction, and intergenerational and historical trauma. In addition to these, we are now living through a world pandemic. The self-isolation, loss of school and social gatherings, socioeconomic impacts and fear may lead to children and families being in crisis. As adults, we are in the midst of trying to figure out different ways to support children now at a distance and when we return to school, in whatever form that takes on.

Traumatized children have a set of problems in the classroom. These include difficulties with attending, processing, storing and acting their experiences in age-appropriate fashion.”

Bruce Perry, 2007

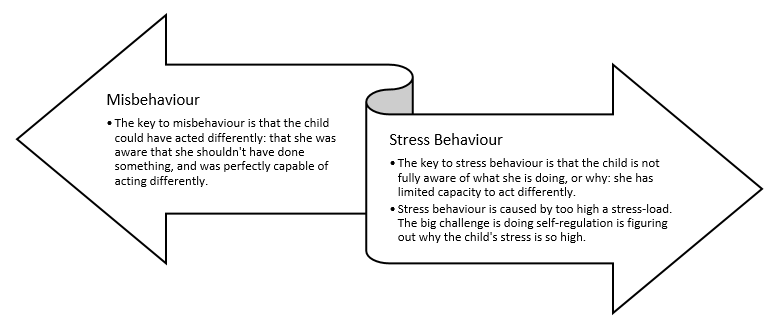

As adults, we are able to reflect on what coping strategies we have created for ourselves to manage our fears and beliefs. By reflecting on how our own coping strategies, we can better understand our students’ behaviours. Sometimes, what presents as misbehaviour is actually a stress behaviour.

To help us understand the involuntary nature of stress behaviour, Nadine Burke shares her research on the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on children.

Dr. Jody Carrington goes further and explains what is happening in a child’s brain when they “Flip Their Lid”.

A brain that has experienced some sort of traumatic event reacts differently than a brain that has developed normally. In fact, Dr. Bruce Perry is one of the many researchers that believes the more threat a brain perceives or experiences, the less intelligent or mindful it is when reacting to stressful situations. A child who has experienced developmental trauma will spend much of of their time, energy and focus on survival rather than on cognition and learning.

So how do we help children create new pathways and patterns to shift their brain to focus on cognition and social emotional learning? This is where teaches are empowered to make a difference.

Planning with the Child in Mind

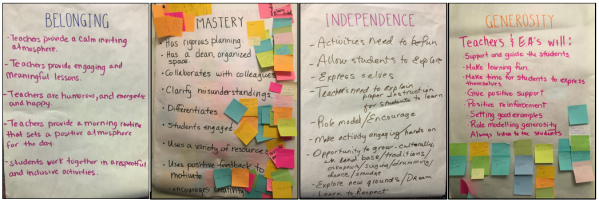

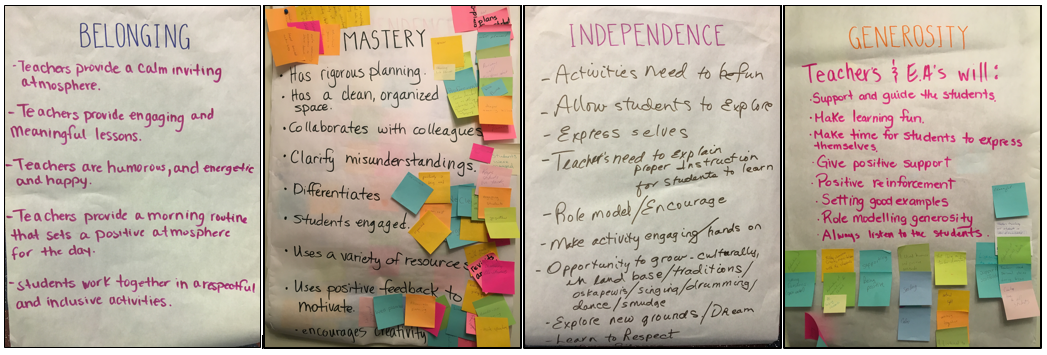

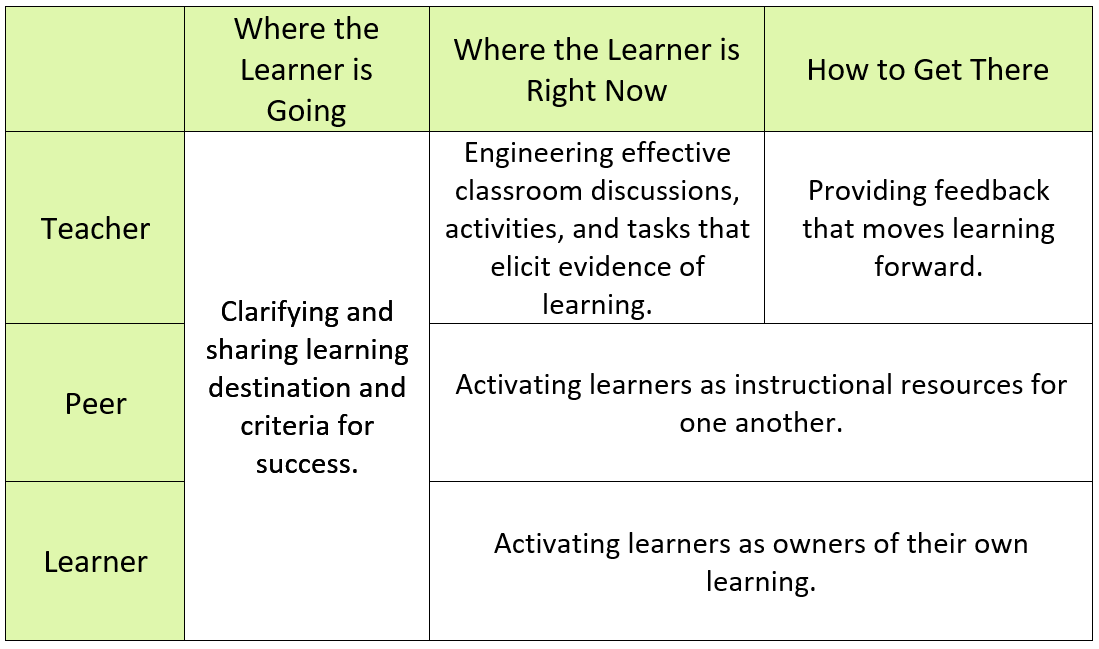

Foundational ideas around what is “good teaching” can create a framework for planning with the child in mind. These include

These key pedagogical ideas all come into play when designing learning backwards from an instructional idea. That idea might come from a child, the class, the community or be some other opportunity to engage in learning in a unique way. Along with content, meaning making and assessment, we can also plan for specific trauma-informed strategies to create new patterns in the brain.

Strategies to Mitigate Trauma

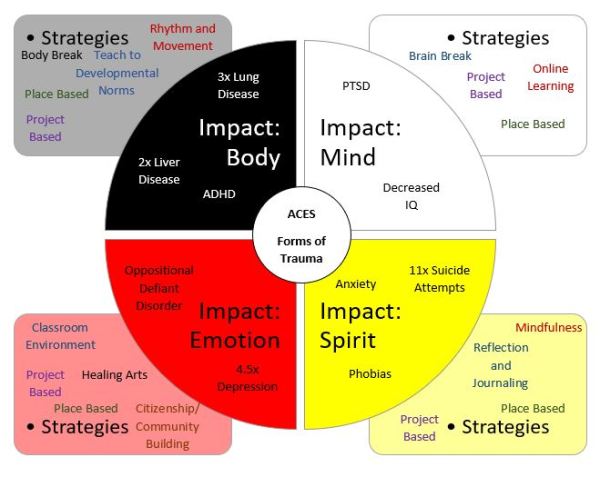

Trauma impacts children’s mind, spirit, emotion and body. therefore, we need to use strategies that create a space for children to heal their mind, spirit, emotion and body.

Classroom Environment

Sask Reads has identified that well-designed learning environments:

- have intentionality and purpose that is carefully planned prior to instruction;

- are functional and adaptable;

- are organized to support the use of instructional approaches, including areas for whole class, small group, and individual learning

- reflect the strengths, needs and interests of all students; and

- are aesthetically inviting to students because their interests, cultures, learning, and work are present within the walls of the classroom.

A trauma-informed classroom environment also might include alternate seating, natural lighting, and places to go where kids can choose to be alone or to be with other people, depending on what they need right then.

Body Breaks

Body Breaks help to promote physical fitness, brain health, focus and cognitive development. Things to keep in mind:

- Body breaks are designed to raise the heart rate and/or use large muscles.

- Body breaks should take no more than 10 minutes 0- ideally they are 2-3 minutes.

- They are often done right at student desks and require little or no equipment.

You can find examples of Body Breaks in this resource summary.

Brain Breaks

Children who have experienced trauma may have compromised brain stem and limbic systems. Brain breaks are specific strategies that can address stress responses, help to develop the brain stem and limbic systems, and activate both left and right parts of the brain. One example of a brain break is tapping therapy.

You can find examples of Brain Breaks in this resource summary.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness can be described as the practice of paying attention in the present moment while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts and bodily sensations.

You can find examples of Mindfulness Strategies in this resource summary.

Self Regulation

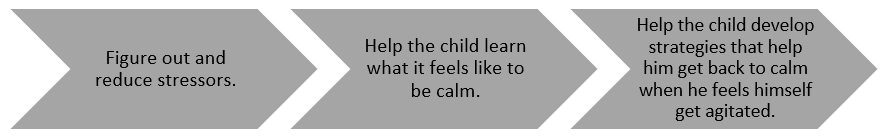

Self-Regulation is a term we use in education, but do not have a shared understanding of what it means. Dr. David Tranter states that “Self-regulation refers to the ways in which people cope with and recover from ongoing stress.” Tranter found that children who have experienced chronic stress have difficulty navigating the demands of the classroom. Children may need support to:

- Monitor their own emotional, physical and mental state,

- Co-regulation techniques where an adult models calming strategies.

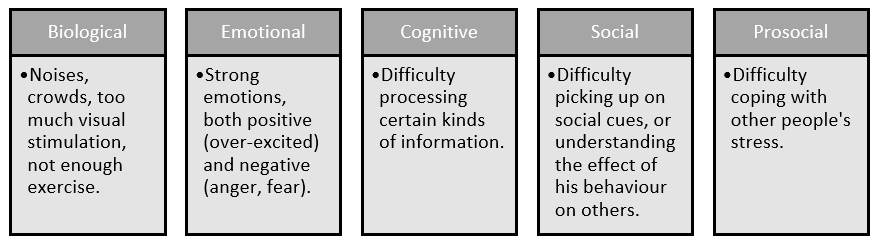

Dr. Stuart Shanker has identified five domains of regulation and strategies to help develop them:

- Biological

- Emotional

- Cognitive

- Social

- ProSocial

Community and Citizenship

Teaching how to be a good citizen and community member is another approach to engage students in deeper learning and build relationships. Through projects and authentic tasks focusing on community building and citizenship, students are given both skills and opportunities to connect to their community in a positive way. Projects and tasks help students find connections cognitively, emotionally, physically and spiritually. These connections help to build positive neural pathways.

In Saskatchewan, the Human Rights Commission has led the development of a “made by teachers for teachers” resource, Concentus Citizenship Education, that connects to our current Social Studies Curriculum and brings citizenship connections to life.

Rhythm and Movement

Trauma treatments that include rhythm, movement and drumming are showing successful outcomes for children who have experienced trauma. Dr. Bruce Perry says we need “Patterned, repetitive, rhythmic, somatosensory activity” to help heal trauma.

You can find examples of Rhythm and Movement Strategies in this resource summary.

Storytelling

Storytelling is a powerful way teaching and learning that helps to build relationships and make connections between ideas. Storytelling is an Indigenous Way of Knowing and predates school and schooling in North America.

You can find examples and information about Storytelling on this resource summary.

Project Based Learning

Project based learning allows students to have control and input into their learning, allows for a focus on relationship-building within the classroom and community, and builds connections between otherwise discreet curricular ideas. Projects are:

- relevant and engaging to students,

- connect and integrate numerous curricular outcomes across multiple courses,

- include formative assessment practices such as self-assessment, goal-setting, monitoring progress and self-determination of changes required.

Chris Clarke, a teacher from Saskatoon, has created a website, Engaged Students, that explores different aspects of a project-based, integrated curriculum course that he teaches in.

Place-Based Learning

Place-Based Learning immerses students in a place’s heritage, culture, landscape. Place lays the foundation for study of language, art, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects.

Place-Based Learning and Land-Based Learning are often confused. The National Centre for Collaboration in Indigenous Education held a digital forum that helped to define land-based learning.

Healing Through the Arts

Art helps kids deal with difficult situations. Painting, beading, drumming, dancing and drama can all access the emotional part of the brain. By observing and talking about the art that they made, they are able to access the left hemisphere of the brain that controls verbal messaging. You can hear more about Art Therapy After Trauma on the Kinds in the House Parenting Website.

By changing our experiences, we can change our brain biology, which impacts our subconscious mind, conscious mind, energy and bodies. It is empowering to know that we can do this for ourselves as well as create a space for children to mitigate the impact trauma has had on their lives.

If you would like more information about how you might have our Growing Resilience Team work with your staff, please contact us.

| Terry Johanson 306-220-9169 | Nancy Barr 306-290-8108 | Kyla Bouvier 306-291-8181 |