Embedded coaches and mentors are a powerful model of professional learning. As colleagues, they work collaboratively with peers to support and extend professional knowledge. Part of working as embedded coaches is to ensure a shared vision and understanding of WHY coaches exist and their impact on teaching and learning.

Embedded coaches and mentors are a powerful model of professional learning. As colleagues, they work collaboratively with peers to support and extend professional knowledge. Part of working as embedded coaches is to ensure a shared vision and understanding of WHY coaches exist and their impact on teaching and learning.

Simon Sinek describes the “Golden Circle”, which has us begin with WHY, and then move to HOW and WHAT. The specific strategies, processes, and structures we use are based on that why.

Based on this theory, coaches can use a Thinking Map to brainstorm together their impact on students, what teachers might do in order to have this impact, what they are doing to support teacher growth and the barriers they are experiencing in their work. From this brainstorm, coaches can define their role collaboratively.

One concern often surfaced by coaches and mentors is that they struggle with beginning a helping relationship with colleagues. How do we start without judging colleagues? How do we ensure that teachers don’t feel that they are being judged as ‘broken’? As helper-leaders, it is sometimes difficult to know how to start.

Simple Truths About Helping

Jim Knight (Unmistakable Impact: A Partnership Approach for Dramatically Improving Instruction, 2011) has identified Five Simple Truths About Helping. These truths might be some of the barriers you are feeling as a coach or mentor with colleagues.

Simple Truth: People often don’t know that they need help

“It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It is that they can’t see the problem.” ~ G. K. Chesterson.

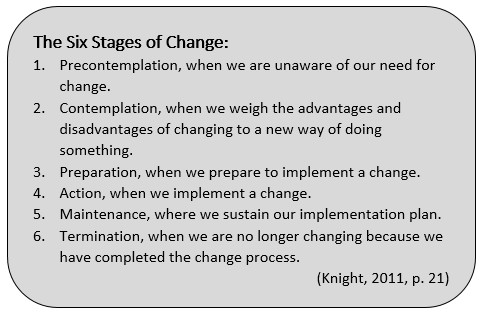

The first step needed for change to occur is to recognize that we need to make a change. As professionals, it is often the case that when we realize that there is knowledge we need to have or a problem we need to solve, we will seek solutions for ourselves. The issue with precontemplation is that we might be blind to the learning or change that we most need to move forward.

Simple Truth: If people feel “one down”, they will resist

Issues related to status in helping relationships are often unanticipated. Coaches often see themselves as helpers rather than having a status that is more or higher than their teacher colleagues.

The very act of helping, Schein (2009) says, puts the coach or mentor “one-up” in a relationship. A teacher, either consciously or subconsciously, will resist being “one down”.

Helping situations are intrinsically unbalanced… Emotionally and socially, when you ask for help you are putting yourself “one down.” It is a temporary loss of status and self-esteem not to know what to do next or be unable to do it (p. 32).

Coaches who are able to recognize that a colleague needs to maintain status will, as Schein says, “equalibrate” their relationship. This involves downplaying their own status and elevating the teacher by calling attention to insights and teaching skills and downplaying their own status and success.

Simple Truth: Criticism is taken personally

“Teacher identities are wrapped up in their perception of their ability to teach.” ~ Jim Knight

Our perceptions and stories of ourselves can be biased slightly in our favour. The narrative in our head protects our self-esteem to explain why we are not meeting our goals. A targeted conversation about teaching practice is not uncomfortable because of what another person may think, it might be uncomfortable because we might have to change what WE think.

Simple Truth: If someone else does all the thinking for them, people will resist

Teachers are knowledge workers, they think for a living. Not only do they think to do their jobs, but they are also creating a learning environment in which their students think. Much like learning in a classroom, professional learning needs to be at a level of appropriate challenge. We know that telling student learners what to do and how to do it stifles the joy of learning. The same is true for adult learners.

Simple Truth: People are not motivated by other people’s goals

“Goals that people set for themselves and that are devoted to attaining mastery are usually healthy. But goals imposed by others can sometimes have dangerous side effects.” ~ Daniel Pink

Research shows that people performing algorithmic tasks, those which you follow a set of steps down a single path to one conclusion, may respond well to extrinsic rewards and punishments. Teaching, however, is a considered to be a heuristic task. Heuristic tasks are those which there is no single algorithm and act as an experiment to create novel solutions. External rewards are not helpful with heuristic tasks, and as Jim Knight notes from Daniel Pink’s research (2009) “they can be “devastating for heuristic ones” (p. 30) because they reduce intrinsic motivation and the value people assign for each task” (2011, p. 27).

According to Pink (2009), there are three factors that can help to motivate people doing heuristic tasks or work:

- Mastery: Doing a job well

- Autonomy: freedom to choose goals and how to achieve them

- Purpose: doing work that is making a difference, being part of something larger than ourselves

The Partnership Principles

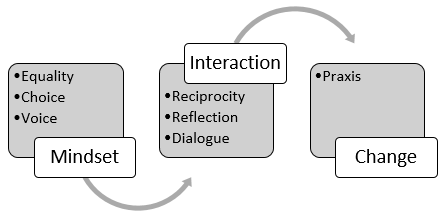

So, what can help with helping? Jim Knight (2011) identifies the Partnership Principles, which are embedded in many of his books about coaching, including his Partnership Learning Fieldbook. Knight’s Partnership Learning Approach (2011) is a collaborative conversation between professionals. Unlike cognitive coaching, partners both contribute to the goals and outcome of the conversation.

“You can get to an understanding of the partnership approach by considering how you would answer a simple question: “If someone was talking with you about your work, how would you like them to relate to you?” Chances are you would want them to treat you as an equal, to respect your knowledge enough to let you make some decisions about how you do your work. You would probably also want them to ask your opinion and listen to your voice, to talk with you in a way that encouraged through and dialogue about your real-life experience. If they also demonstrated that they expected to learn from you, it would probably make it all the more likely that you would listen to them.” (Knight, p. 28)

Equality: Learning With Rather Than Done To

Equality is central within any partnership. Partners do not decide for each other; they decide together. In a true partnership, one partner does not tell the other what to do; they discuss, dialogue, and then decide together. Partners realize in healthy partnerships they are a lot smarter when they listen to their partner- when they recognize their partner as an equal.

Learners who embrace the principle of equality recognize that in a partnership, the goal is not to win the other side over to their view. Rather, the goal is to find a match between what they have to offer and what a teacher can use. In the truest sense, if someone does not agree with our view of the world or our perspective, in a partnership the first step is to not argue our point more persuasively but to try to fully understand the collaborating teacher’s view or perspective. (Knight, 2011)

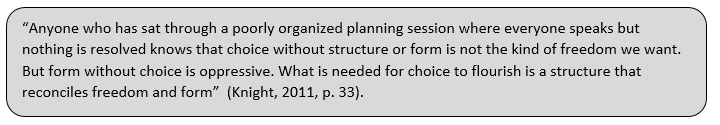

Choice: What and How They Learn

“Teachers should have choice regarding what and how they learn” (Knight, 2011, p. 31). If we believe in professional equality then it follows that all professionals have the right to make decisions regarding what and how they learn. When change leaders do not provide choice to professionals, it immediately negates a sense of equality and can promote a sense of “one-up” that can erode a sense of professional equality. Just as with learners in a classroom, a complete choice is not possible. Complete freedom is not the answer, as there are times when a school or system needs teachers to have a shared understanding and implementation of teaching practices.

Voice: Learning Empowers and Respects all Voices

“If partners are equal, and if they choose what they do and do not do, they should be free to say what they think, and their opinions should count” (Knight, 2011, p. 34). When learning in partnership, all voices are equally respected. “When we take the partnership approach, we create opportunities for people to express their own points of view. This means that a primary benefit of partnership is that everyone gets a chance to learn from others because others share what they know” (Knight, 2011, p. 34).

How does this impact coaching? Jim Knight (2011) has some suggestions:

- Enter into conversations by asking questions, and wait for others to say what they think;

- Temporarily set aside your own opinions so you can really hear what others have to say;

- Truly value your colleagues’ perspectives;

- Enter conversations expecting to learn from your colleagues; and

- Effective practices are shared rather than mandated, allowing teachers to make connections and figure out how to implement in their context. Tools that empower teachers to be more organized, have a deeper understanding of content and process and connect to more students can inform teacher voice.

Reciprocity: Everyone Learns

Reciprocity is the belief that each learning interaction is an opportunity for everyone to learn – an embodiment of the saying, “when one teaches, two learn.” People who live out the principle of reciprocity approach others with humility, expecting to learn from them. When we look at everyone else as a teacher and a learner, regardless of their credentials, we will be surprised by new ideas, concepts, strategies, and passions. If we go into an experience expecting to learn, much more often than not, we will.

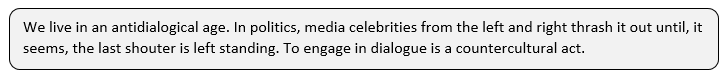

Dialogue: Thinking Together

Dialogue is a sign that we truly respect our partners. Dialogue is talking with the goal of digging deeper and exploring ideas together, or “thinking together”. Paulo Freire describes dialogue as a mutually humanizing form of communication. We become more thoughtful, creative, and alive when we talk in ways that open up rather than shut down.

As Martin Buber (1970) explains, if I use language to get people to do what I want them to do, if I manipulate, then I treat them like objects, not subjects. An antidialogical approach is truly dehumanizing. It is only when I encourage and tap into my partner’s imagination, creativity, knowledge, and ideas, that I truly respect them as fully human.

Reflection: Accept or Reject Thinking

When we take the partnership approach, we don’t tell others what to believe; we respect our partners’ professionalism and provide them with enough information so they can make their own decisions. Partners don’t do the thinking for their partners. Rather, they empower their partners to do the thinking. Reflection stands at the heart of the partnership approach, but it is only possible when people have the freedom to accept or reject what they are learning as they see fit.

When we take the partnership approach, we don’t tell others what to believe; we respect our partners’ professionalism and provide them with enough information so they can make their own decisions. Partners don’t do the thinking for their partners. Rather, they empower their partners to do the thinking. Reflection stands at the heart of the partnership approach, but it is only possible when people have the freedom to accept or reject what they are learning as they see fit.

Praxis: Apply Learning to Real-Life Practice

The ultimate goal of all forms of professional learning is for teachers to apply their learning in their contexts. In a partnership approach, how this occurs is that teachers are given time to reshape new ideas, integrate them into existing practices and implement ideas in a way that makes sense. Praxis is defined as the say that we apply new ideas into our lives. This is the foundation for change in education.

In order for praxis to occur, teachers need to consciously decide to implement or not implement and in what ways. They need to make sense of the idea and connect it to their prior learning. Praxis is not memorizing a new routine or using a new program. Praxis is a conscious choice to make conscious decisions regarding teaching practice.

Having the skills to build learning relationships with teacher colleagues is key to the effectiveness of coaches and mentors. Professional relationships and a clear vision for WHY we do this work can build positive learning-focussed conversations that move learning forward for both teachers and coaches, and ultimately provide supports for students in our classrooms.

Knight, J. (2002). Partnership learning fieldbook. Retrieved Mar 15, 2012, from Instructional coaching Kansas coaching project: http://instructionalcoach.org/images/partnership/PartnershipLearningFieldbook.pdf

Knight, J. (2011). Unmistakable Impact: A Partnership Approach for Dramatically Improving Instruction. Thousand Oaks: Corwin, Learning Forward.

Schon, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Washington.