Classroom management is the part of teaching that is invisible when it is working well, and highly visible when we and our students are struggling. Sometimes it may feel like herding cats:

Classroom Management’s purpose is to “provide structure while helping students develop autonomy, awareness and self-regulation skills” (Emerich France, 2018).

Traditional classroom management theories rely on teachers viewing student behaviour as a matter of choices or intentional defiance. As a result, traditional solutions have been a list of consequences and rewards. While consequences may be a part of a classroom management plan, if the goal of classroom management is to have students understand themselves and self-regulate, teachers and students need to first identify the causes of behaviours, attempt to prevent triggers and increase self-awareness.

General principles of Discipline with Dignity (Curwin, Mendler, & Mendler, 2018) are:

This perspective of classroom management allows us to link the effects of trauma and brain development to understanding some of the underlying causes of student behaviours. Classroom management is founded on knowing our students and building relationships with them.

Basic Needs that Drive Behaviour

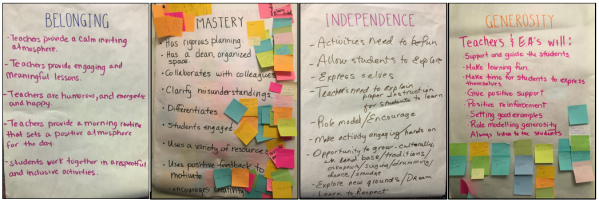

Curwin, Mendler, and Mendler (2018) and Dr. Martin Brokenleg (Circle of courage, 1990) have identified what our and our students’ basic human needs are in order to be healthy and whole.

| Curwin, Mendler, and Mendler | Dr. Martin Brokenleg |

| Identity – “how we view ourselves and how we feel about ourselves” | |

| Attention – “the need to be acknowledged by others in a way that makes us feel that we matter” | Generosity – to give our knowledge, skills, insight, experience, and resources to others; receiving a sense of purpose from strengthening the community |

| Connection – “our need to feel that we belong to something that matters to us” | Belonging – to feel valued, affirmed and significant within the group; believing in the importance of a shared purpose; to identify with shared goals |

| Competence – “feeling that we know how to do something” | Mastery – to develop abilities, skills, and knowledge in order to take risks, to try new things and learn from others; to embrace challenges and learning |

| Control – “the desire to make decisions that count, to have real choices, to control our environment” | Independence – to feel in control of our learning; to have a sense of competent autonomy and to contribute to responsibility |

Saskatchewan teachers and educational assistants used a Circle of Courage graphic organizer to brainstorm what they need to keep in mind to create a learning environment that fosters a sense of belonging, mastery, independence, and generosity in their students:

A school environment that provides opportunities for students to have their needs met is part of a “prevention mindset” (Curwin, Mendler, & Mendler, p. 61). Looking at prevention from the student perspective, appropriate behaviour is generally achieved when students:

- Feel connected to the teacher, one another, and the curriculum.

- Believe that success is attainable with reasonable effort.

- Feel respected by being heard; feel teachers strongly care about them in personal ways.

- Are given responsibility, especially in helping other children. This involves giving appropriate choices throughout the day.

- Look forward to sanctioned moments of joy and laughter every day.

- Believe that what is being taught is relevant.

Activating Peers as Learning Resources

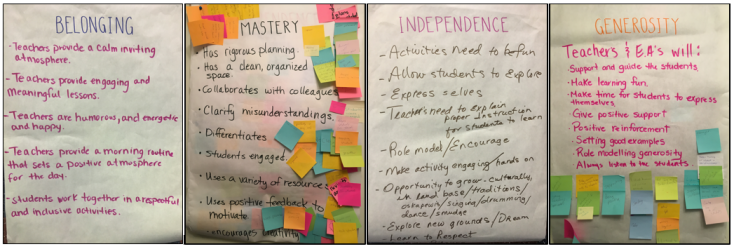

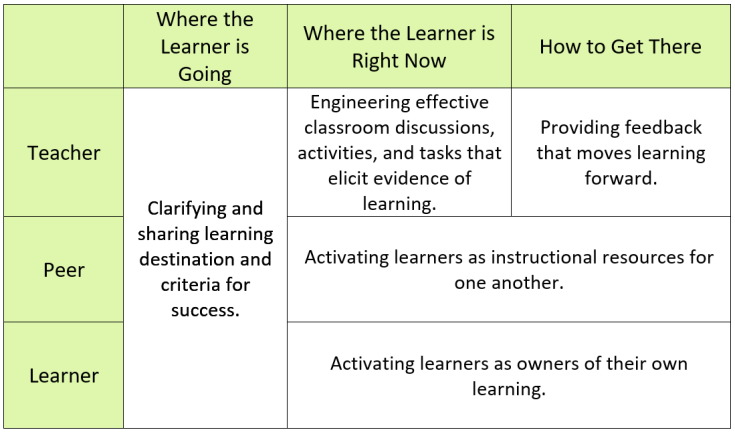

Dylan Wiliam has identified five strategies for Formative Assessment, which increase student engagement and achievement.

Wiliam’s work guides our instruction in many ways, including how to activate learners as instructional resources. Collaborative learning that encourages group goals and individual accountability is more powerful than simply having students work on tasks in a group. This group work increases student sense of belonging and provides a space for generosity within a community of learners.

Wiliam (2011) identifies why students benefit from helping their peers:

- they are working towards a common goal and they benefit from the efforts of all, resulting in increased motivation.

- they care about their group members, resulting in social cohesion.

- they understand and can address the difficulties their peers are having, resulting in personalization.

- thinking together brings clarity, resulting in cognitive elaboration.

Assessment Strategies

Wiliam writes about a number of strategies that can enhance peer support of learning within a classroom.

In his book Embedding Formative Assessment, Wiliam suggests many strategies, including:

- Peer Evaluation of Homework – The class or teacher create criteria (rubric) for the work. Who is assessing the work changes and is not announced until the homework is complete. Evaluators may be: Self, Other – individual or group or Teacher

- Two Stars and a Wish – student feedback on other students’ work – 2 positive qualities and a suggestion for improvement; Teacher needs to instruct students on what quality feedback looks like. Sentence starters can be useful to give to students in advance.

- Preflight Checklist – When there are specific requirements or features of a piece of student work, this list is checked by a peer prior to the work being handed in. If there are pieces missing that were on the checklist, the peer is the one held accountable.

- Group-Based Test Prep – Within a group, each student is assigned a different part of a unit to review. They prepare and present their review to their group. Peers assess the review using coloured cups (red – not as good as I would have done; yellow – about the same as I would have done; green – better than I would have done).

Teaching and using group work goes beyond learning styles, and can enhance student motivation, engagement and resilience.

Stress Behaviours

(Adapted from The Mehrit Centre’s Infographic on Understanding Stress Behaviour for Teachers)

Brain research has shown that there are differences between stress behaviours and misbehaviour. If we treat them in the same way, it can be hard on our students and hard on ourselves.

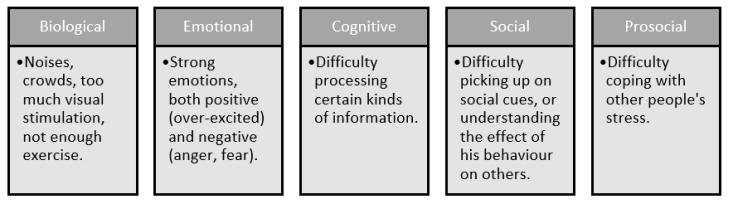

The 5 Primary Domains of Stress

There are many different reasons why a student might show signs of stress behaviour. These are linked to Shanker’s five domains of self-regulation.

Signs of Stress Behaviour

Stress behaviours (Shanker, 2018) are biological in nature and neither intentional nor conscious choices on the part of students. These might include:

- Heightened impulsivity

- Difficulty ignoring distractions

- Problems in mood (sees everything negatively)

- Erratic mood swings

- Trouble listening

- What she is saying doesn’t make sense

Dealing with Stress Behaviour in Students

When a child exhibits stress behaviour, what do we do as educators? Shanker (2018) suggests that we:

Along with specific calming strategies that can help students, include mindfulness strategies and ways to integrate social-emotional learning throughout the day.

Effects of Early Trauma

“Trauma has a powerful capacity to shape a child’s physical, emotional, and intellectual development, especially when the trauma is experienced in early life” (JBS International and Georgetown University National Technical Assistance Centre).

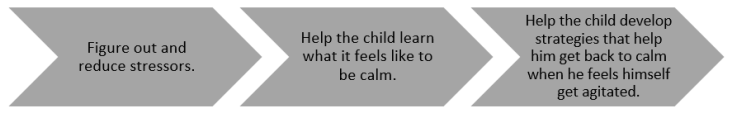

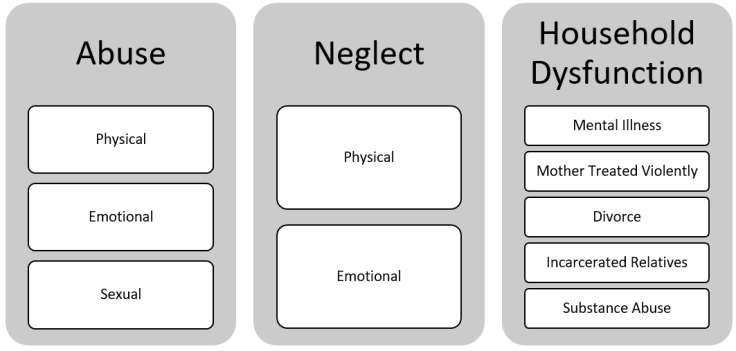

Three Types of ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences)

There are significant impacts of ACEs on individual health outcomes. Brain science has determined that ACEs disrupt neurodevelopment, which leads to social, emotional and cognitive impairment, adoption of health-risk behaviours, disease, disability, and social problems and eventually can lead to early death.

Continued exposure to trauma creates an environment filled with relentless fear, resulting in the development of a self-defence mechanism in a child’s brain that requires a fight, flight or freeze response. Stress responses are maintained due to:

- A persistent fear response that ‘wears out’ neural pathways;

- Hyperarousal that causes children to overreact to non-threatening triggers;

- Dissociation from the traumatic event in which the child shuts down emotionally; and

- Disruptions in emotional attachment, which can be detrimental to learning.

(JBS International and Georgetown University National Technical Assistance Centre).

Intergenerational and Historical Trauma

The Georgetown University National Technical Assistance Centre for Children’s Mental Health has identified two types of trauma that may have an impact on children in schools:

- Intergenerational trauma results when disturbing experiences have not been addressed and their emotional and behavioural legacy is passed down from parents to their children. Parents who experienced persistent trauma in childhood may struggle with their own ability to express empathy, compassion, and self-regulation. Unresolved trauma may make it difficult for parents to build trusting relationships and healthy attachments. This trauma is then transmitted to future generations.

- Historical trauma goes beyond a single family to a community caused by historical, systematic abuse and injustice. In additional to family-specific intergenerational trauma, historical trauma may also result in shame and loss of culture and identity. The legacy of historical trauma can result in “repression, dissociation, denial, alcoholism, depression, doubt, helplessness, and devaluation of self and culture”.

Brain Malleability

While trauma affects brain development, causing structural and hormonal changes, the malleability of the human brain brings us hope. Because the brain can heal, and new neuropathways can be developed, teachers and schools can impact the long-term social, emotional and physical impacts of trauma. Trauma-informed schools are those where the school climate, instructional designs, positive behavioural supports, and policies are created so that traumatized students have what they need to achieve academic and social competence (Craig, 2016).

| PBIS – Positive Behavioural Interventions and Supports | SEL – Social Emotional Learning |

| The goal of PBIS is to create a positive school climate, in which students learn and grow. | A process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions. |

Dr. Bruce Perry has done significant research in the area of mitigating the impact of trauma on children.

Dr. Perry contributes to the Child Trauma Academy, which makes a number of free resources available.

Solutions in classrooms directed at brain stem activity can help create new pathways in the brain’s cortical areas. These include

- patterned rhythmic activities

- walking

- dancing

- singing

- meditative breathing

- create a calmer cognitive state so higher order thinking can occur

- scaffold new information on prior knowledge

- use classroom discourse purposefully

- peer collaboration

- provide direct instruction

Instruction and school environments that provide calming opportunities can help children learn to be more self-aware and foster their own emotion regulation, which then impacts the behaviour-consequence cycle.

As teachers, when we understand the underlying causes of student behaviour, we can not only respond, we can avoid triggers. Classroom Management is more than just the strategies we use, it is the relationship and understanding of the children we teach in order to help children build new neural pathways, understand their own behaviour and learn to self-regulate.

When and Where to Refer Students?

Sometimes, we might recognize that one of our students requires additional supports. Central Office personnel or support teachers may be able to help you assess where your students are at. For parents, Amy Morin writes about some of the indicators that a child might require targetted services in her blog post “When Should Parents Seek Help for a Child’s Behavior Problems?”. Supports from outside of your school system may be available through your regional health authority, which is listed on the Saskatchewan Health Authority’s Website. In the Prairie North Health Region, for instance, there are a number of youth-focussed supports in North Battleford.

Works Cited

Brendtro, L., Brokenleg, M., & Van Bockern, S. (1990). Circle of courage. Retrieved February 14, 2014, from Reclaiming youth international: http://www.reclaiming.com/content/aboutcircleofcourage

Craig, S. E. (2016). Trauma-Sensitive Schools: Learning Communities Transforming Student Lives K-5. New York: Teachers College Press.

Curwin, R. L., Mendler, A. N., & Mendler, B. D. (2018). Discipline with Dignity: How to Build Responsibility, Relationships, and Respect in Your Classroom. Alexandria: ASCD.

Emerich France, P. (2018, September). A Healthy Ecosystem for Classroom Management. Educational Leadership, 76(1). Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept18/vol76/num01/A-Healthy-Ecosystem-for-Classroom-Management.aspx

JBS International and Georgetown University National Technical Assistance Centre. (n.d.). Issue Brief 1: Understanding the Impact of Trauma. Retrieved from https://gucchdtacenter.georgetown.edu/TraumaInformedCare/issueBrief1_UnderstandingImpactTrauma.pdf

Shanker, S. (2018). (The MEHRIT Centre) Retrieved August 18, 2018, from Shanker Self-Reg: https://self-reg.ca/

Sousa, D. A. (2009). How the Brain Influences Behaviour: Management Strategies for Every Classroom. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded Formative Assessment. Bloomington, Indiana, United States of America: Solution Tree Press.